Anachronisms and the ‘Okay’ problem

When writing High Fantasy, one of the challenges is to maintain a certain level of diction. By this, I mean the sort of language used in the body text and in the dialogue of the characters. It comes down to vocabulary and sentence structure in the end, and with the usual quasi-medieval setting of most High Fantasy this means a certain old-fashionedness in language.

When this is done in a ham-fisted way, we get the sort of ‘forsoothery’ that quite rightly prompts parody, with characters flinging about ‘thee’ and ‘thou’ with no understanding of how these pronouns actually work, and then jamming in a ‘ye olde’ here and there – again with no understanding of what a howler that construction is.

What the writers of the best High Fantasy strive for is to achieve a consistent level of old-fashioned language, one that gives the illusion of being archaic. There are many ways to do this, but one of the simplest and best is to avoid anachronisms.

Anachronisms, in this sense, are words or expressions that are too modern for the setting of the story. Good vocabulary choice inveigles and seduces a reader into the old-fashioned world of the story. Bad vocabulary choice – anachronistic language – jars a reader out of the story, which is a bad thing indeed.

Many, many years ago I came across a stark example of this in a Choose Your Own Adventure book. Things had been going along well, with a mixed adventure party (elves, dwarves, humans) pottering about meaningfully in a perfect medieval castle, and then they met a party of bloodthirsty goblins. That’s when the chief elf uttered the immortal words: ‘Let’s make hamburger out of them!’

Even though I was a naïve reader, and without quite knowing why, I shuddered at that. I put the book down, completely taken out of the story and unwilling to continue – an outcome every writer wants to avoid.

How to avoid anachronisms? A good historical dictionary is most useful, one that cites the first appearance of a word, but more important is a sensitivity to language. When writing in this mode, a writer simply must understand that language changes, that how we speak today isn’t the way people spoke years ago. Reading texts – novels, plays, poetry – from centuries past can be helpful. ‘Is this the best/most appropriate word?’ should be a standard question every writer asks of his or her own work. Building up a list of words that are perfect, contextually, is a good strategy. When reading, I’m always alert for such words and I have a number of such lists, each one pertaining to a particular time frame.

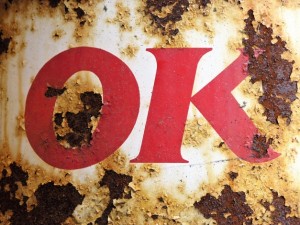

This brings me to the vexed question of ‘okay’. This might be personal, but no other words screams modernity more than ‘okay’. It sounds so contemporary, so urban, so up to date, that every time a bold knight or cunning sorceress says, ‘Okay’ I groan.

And this is even though I know that ‘okay’ isn’t as modern as I feel it is. It has a reasonably venerable history going back to the early 1800s, even though its precise organs are hotly contested. And I realise that most of the other words a writer uses aren’t historically accurate either, but my contention is that some words are signifiers, that they are language landmarks where a writer stakes her or his claim to authenticity. When ‘okay’ appears in a High Fantasy book, it’s like an atomic-powered killing machine appearing in Pride and Prejudice.

To my mind ‘Okay’ is out of place in High Fantasy, and using it is a mistake.

I found this article very apt for me, as I’m starting to develop a project I’ll be undertaking for study later this year and it’s a high fantasy.

Making a list of words is such a great idea. Thank you, Mr Pryor!