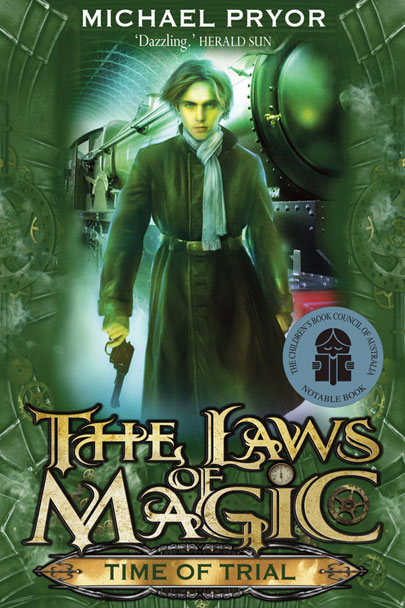

TIME OF TRIAL

Time of Trial – Michael Pryor

Time of Trial – Michael Pryor

To buy Time of Trial, go here.

Cover blurb

The mysterious Beccaria Cage could be the cure for Aubrey’s condition: a way to reunite his body and soul. But could its usefulness hide something more sinister?

After Aubrey narrowly escapes the worst fate he can imagine, he realises that there is only one thing to do: he must confront his nemesis. With George and Caroline at his side, he travels to Holmland – the home of Dr Tremaine and the heart of hostile territory – only to face magical conundrums, near-death experiences, ghosts, brigands and enemies on their own ground.

Fisherberg is a city on a knife edge. Can Aubrey solve its mysteries before Dr Tremaine’s warmongering machinations tip the world into chaos?

Michael Pryor says

Time of Trial is a turning point for Aubrey, George and Caroline. Political matters are coming to a head and after Dr Tremaine stretches out his hand and strikes from afar, they realise that they must act – instead of waiting for events to unfold.

As Book 4 of a six book series, Time of Trial is vital in keeping the narrative arc going while maintaining the character and relationship development. This means hurdles must be met and overcome (or not …) and more challenges coped with. I didn’t want Time of Trial to be ‘more of the same’ so it struck me that the best way to emphasise this would be to have the characters shift ground, moving from Albion to somewhere else. They’d already been to Gallia, so I was stuck – until I considered the possibility of their going to Holmland. In this tense pre-war period, travel would still be possible between countries, and I found many historical examples of this, with both diplomats and academics moving between countries with some freedom.

I also wanted the relationship between Aubrey and Caroline to be tested – again. I like the way that they’ve reached an accommodation, but sometimes the head and the heart don’t necessarily talk to each other as they should …

Time of Trial begins

Aubrey Fitzwilliam braced himself for the next attack from his young, tall and menacing adversary. Young and tall were manageable. It was the menacing part that was the problem.

Aubrey grimaced as sweat trickled from his brow and threatened to blind him, but he couldn’t spare a hand to wipe it away.

His adversary advanced on him, murder in his eye, and launched a thunderbolt.

Aubrey played forward and had to jerk back when the ball leaped up off a good length, whistling past his gloves with nothing to spare.

The bowler stifled a groan and stood mid-pitch. He threw his head back as if to berate the gods for the injustice. Then he scowled at Aubrey before beginning his march back to his bowling mark.

Aubrey straightened and removed his batting gloves, trying to give the appearance of someone who had so much composure that he could give the surplus away to those less blessed — while inside, his batting nerves jittered alarmingly.

The annual match between St Alban’s College and Lattimer College was a carnival, the traditional event to mark the end of term. Surrounding the oval was a throng of vastly amused spectators, as well as a brass band, a coconut shy, sundry vendors of refreshments, assorted dogs and even a tethered hot air balloon for the amusement of those not entirely interested in the cricket. The day was bright and sunny, perfect weather for such an occasion.

Aubrey was batting much sooner than he’d expected. Coming in at number eight after a pitiful collapse by the higher order, he was attempting to gather the sixty-odd runs needed for victory. If he managed this improbable event, St Alban’s would defeat Lattimer College for the first time in thirty-four years. At the moment, this was exceedingly unlikely, as it seemed to Aubrey as if Lattimer College was solely populated by six-foot-tall Adonises. Every one of their bowlers had shoulders so broad that he imagined Lattimer College was built with extra-wide doorways, to save these gargantuan athletes from having to turn sideways to enter rooms.

Aubrey’s batting partner, by contrast, was a well-meaning, second-year magic student whose mind was mostly elsewhere. He had a disconcerting habit of blinking and saying, ‘My word. Should I be running now?’ when Aubrey was haring toward him, which hadn’t helped matters at all.

The umpire cleared his throat. He was the professor of Jurisprudence, selected on the misunderstanding that a familiarity with the law meant he’d be a good umpire: His extremely thick glasses suggested otherwise. ‘Are you ready, young man?’ he quavered down the length of the pitch.

Aubrey sighed. ‘Sorry, sir.’ He pulled on his gloves. Bat and pad close together, he thought, and if it’s loose, lash it through the gap in the offside.

Aubrey hadn’t had a loose delivery in the four overs he’d faced, but he was doing his best to be optimistic.

The bowler pawed the ground impatiently. From where Aubrey stood he seemed small against the jollity of the spectators behind him. Parasols, straw boaters and striped blazers made a colourful backdrop, and Aubrey knew he’d lose sight of the ball as soon as the bowler hurled it.

He went into his stance and gripped the bat so tightly it hurt.

The bowler squared his shoulders, his shirt visibly straining not to burst at the seams. He grinned, then set off. At first he loped, easily and smoothly, like a steeplechaser. Soon, however, he accelerated, arms and legs pumping, a maniacal grin on his face.

Just as the bowler gathered himself for his huge final bound and delivery, Aubrey straightened. He smelled something — something more than the smell of mown grass, more than the tang of nervous sweat, something different from the aroma coming from the pie seller’s barrow.

He smelled shrillness — and he knew magic wasn’t far away.