Writers Write: My Favourite Book 30

Claire Corbett

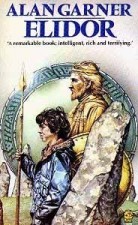

The book that haunted my childhood was Elidor by British writer Alan Garner. An icy, grief-stricken story overshadowed by the twilight feel of Celtic myth, it was a short sharp shock after the cosiness of the Narnia tales I knew and loved. Elidor was the first book to shatter my childhood expectations of happy endings, to unsettle me with the power of elision and loss. Garner, an elusive writer considered among the greatest fantasy writers, experiments with how much of plot and character he can pare away and still have a story standing. My childhood copy of Elidor, (the Fontana Lions edition illustrated by Charles Keeping) which I still own and treasure clocks in at a bare 160 pages.

Set in the bombed, rubble-strewn streets of post-war Manchester, Elidor is the perfect post-war British fantasy evoking exquisitely so much that has been destroyed, that has vanished forever.

Four siblings, Nicholas, David, Helen and Roland Watson, are drifting around central Manchester. Children of a different era, they are without money (or mobile phones, of course) or adult supervision. Their family is moving house and, banished out of the way by their parents, they are searching for something to do. They find their steps seemingly directed to a street where houses and a church are being demolished. The bombed church is the gateway through which the children find themselves in Elidor, the Green Isle of the Shadow of the Stars.

But Elidor is no Magic Faraway Tree or Narnia, a place of exhilarating adventure. Elidor is dying. Like Manchester, it has been attacked by faceless evil. Malebron, its wounded king seemingly without an army or any subjects, turns, inappropriately, to the four bewildered children for help. Like the beleaguered adults in the real world who were forced to fight World War Two, he is unable to shield the children from the harsh reality of war or even to explain it.

‘The darkness grew,’ said Malebron. ‘It is always there. We did not watch, and the power of night closed on Elidor. We had so much of ease that we did not mark the signs – a crop blighted, a spring failed, a man killed. Then it was too late – war, and siege, and betrayal, and the dying of the light.’

This is no explanation at all, despite the echo of Dylan Thomas in the last line, but it is all the explanation for evil that any of us are ever likely to get.

Roland, the youngest of the children and derided for his dreaminess finds that in Elidor his imaginative power is ‘real as swords’ and so the heaviest burden of saving Elidor falls on him. The novel’s epigraph, Childe Rowland to the Dark Tower came, is a line from King Lear, which refers to a fairytale in which Childe Rowland rescues his sister, Burd Ellen, from the King of Elf-land. In the novel, each child is encumbered with a treasure – a stone, a spear, a sword and a cauldron. Malebron insists the children must protect the treasures in our world in order to keep Elidor alive while they, and all Elidor, wait for the mysterious Findhorn who alone can save the land.

When I first read Elidor, at around age seven or eight, I was baffled and haunted by its spareness. It was my first experience of how restraint hooks the reader. I wanted to know more. I needed to know more: more about Elidor, about the evil Mound of Vandwy, about the magical Findhorn. In negative reviews of Elidor readers voice exactly these complaints. Elidor is too spare, too mysterious, the reader spends too little time there. It’s true that Elidor is not The Lord of the Rings. Garner doesn’t give us a whole other reality to luxuriate in. We search the book for the world hidden behind and within the words and this obsessive search ensures that many sentences in the book become burned into the mind. These complaints about Elidor illustrate how brilliant the story is and how the writing subverts the idea of fantasy as escape.

It was the collision of the other world of Elidor with (relatively) modern Manchester that excited me so as a child. Garner did his science homework and the scenes using electricity as the analogue of Elidor’s magic in our own world are the most frightening. The framing story for Narnia was set in a past that to me as a child was almost as remote as the Middle Ages. The Lord of the Rings is of course an entirely other world, one in which technology has not entered the industrial age (though the portrayal of Isengard does seem to be a critique of the Industrial Revolution).

To see Elidor invade the world I recognised, where children watched television while they did their homework, was to experience the most potent fantasy, in which wonder and horror stalk the domestic, the ordinary, the everyday. Writing this now, I realise that Elidor has been one of the most powerful influences on my own work, that I too am most interested in writing about the reality we know, here and now, but a reality spiked with unexpected shards of beauty and horror.

The end of Elidor is perfect, devastating. Like The Lord of the Rings, and unlike so much heroic fantasy, Elidor shows the hollowness of victory, the price of trying to make whole that which can never be restored. Elidor resonates in an adult register; you may defeat the darkness but the price will be higher than you can bear.

Helen mended the jug she had found in the hole. It was a large pitcher, and it had broken into five pieces. She spent hours glueing them together, almost in tears when she thought of what she had done. The pitcher had lain in the ground such a long time, and such a little care would have saved it. Now she was too late, and nothing could make it whole again.

Claire’s novel ‘When We Have Wings’ was published by Allen & Unwin in July 2011 and shortlisted for the 2012 Barbara Jefferis Award. It is also being published in Spain, Portugal, The Netherlands and Russia and has just been released as an audiobook by Bolinda Publishing. For more, visit Claire’s website.

Claire has also just announced a giveaway happening on GoodReads until August 31st. Be in it!

Thanks for asking me to write this, Michael. It sparked a lot of thoughts and feelings I didn’t know I had.